La valse hesitation: Part I Adult Attachments

- Amy Baker

- Feb 13, 2018

- 3 min read

Updated: Apr 26, 2018

The Hesitation Waltz was a real thing back in the 1903-1910 range of time. It got its name from the pause, or "hesitation," in the actual music, but it went out of fashion quickly because it was considered too complex for the average dancer.

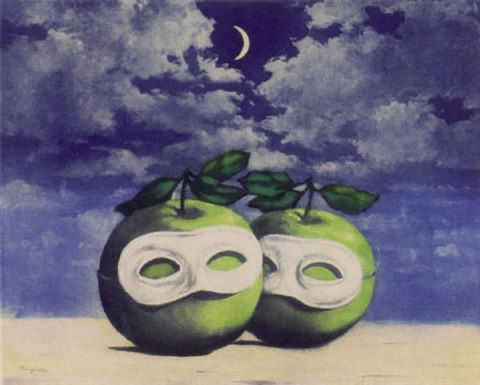

What an apropos metaphor for the post-modern dance of relationship. It also is a difficult dance, still popular to start learning, but abandoned after about 4-7 years for about 50% of those who begin to learn the dance.

We want this proximity and closeness or sex--often both. We are drawn to want this. It is an innate human need that starts in the womb during fetal, brain, and hormonal development. It is expressed in infancy by a baby's cries for its primary caregiver(s), and how that caregiver responds shapes our attachment style, which has been thought to remain stable throughout the lifespan.

Although the field of Attachment in developmental psychology has been around since the 40s, 50s, and 60s, it was truly groundbreaking work of John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth when they mapped out human needs from infancy:

Attachment Theory in Infancy and Early Childhood:

proximity and responsiveness from the primary attachment figure makes the one longing for closeness to feel safe

both the child and the caregiver engage in close, intimate, bodily contact

both feel insecure when the other is inaccessible

both share discoveries with one another

both play with one another's facial features and exhibit a mutual fascination and preoccupation with one another

Repeated interactions with an available attachment figure usually result in the development of positive beliefs about oneself as being worthy of love and positive expectations about the attachment figure as being reliable and supportive. When a child gets his or her needs met readily by a caring and nurturing primary caregiver, the child is likely to develop a secure attachment style. When the child does not get his or her needs met readily by a nurturing primary caregiver, or that care is given intermittently, or that care is given aggressively or violently, what often develops is an insecure attachment style that is based on the care provided by the child's mother, father, or other primary caregiver. When needs are met intermittently, a child is likely to develop an anxious-ambivalent attachment style. When the child experiences neglect or anger and discompassion from the caregiver, they may become more avoidant. When a child experiences both intermittent positive and negative responsiveness combined with neglect and aggression, the child is likely to develop what is known as a disorganized attachment style, which combines Avoidant with Anxious-Ambivalent.

The attachment system is commonly described as an emotion regulation device that is oriented toward distress alleviation and includes different strategies to regulate negative emotional experiences. Until recently, the attachment style a person developed in infancy and early childhood was largely thought to remain stable throughout the lifespan.

In 1987, Shaver and Hazan discovered that the attachment style a person develops in infancy and early childhood looks much the same in adult attachment style, and that attachment itself runs through the course of a lifespan and plays out in relationship. Romantic love can be regarded as an adult version of the affectional bond between infants and their caregivers.

As in infancy and childhood, the adult intimate couple represent two individuals involved in an exchange of intimate energy with one another as attachment figures in one another's life. In individuals with a secure adult attachment style, repeated positive interactions with one another results in positive beliefs about oneself as being worthy of love and positive expectations about the partner (attachment figure) as being reliable and supportive. However, when the partner is perceived as being unavailable and unresponsive, feelings of insecurity continue to exist, leading people to adopt alternative strategies for dealing with distress which coincides with the development of negative beliefs about the self or the other, characteristic of anxiously and avoidantly attached individuals (Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998). Although both anxious and avoidant attachment are commonly referred to as insecure attachment, each style is associated with a distinct way of regulating distress.

Secure Attachment in Adulthood

Each individual within the couple feels confident that their partners will be there for them when needed, and open to depending on others and having others depend on them.

Insecure Attachment in Adulthood

Anxious-Ambivalent

An insecure partner with an Anxious-Avoidant attachment style may worry that the other may not love them completely, and be easily frustrated or angered when their attachment needs go unmet.

Avoidant Attachment in Adulthood

An Avoidant partner may appear not to care too much about close relationships, and may prefer not to be too dependent upon other people or to have others be too dependent upon them.

Comments